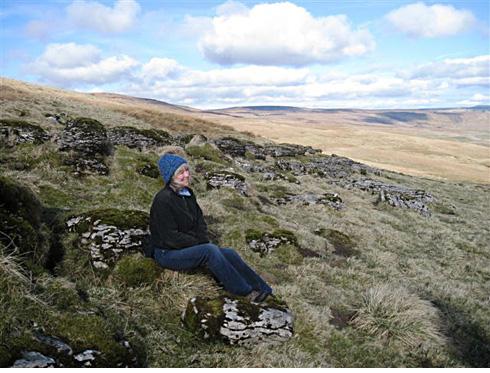

In the beginning... When I was born at home on the moors outside a tiny village in the Yorkshire Dales called Wigglesworth, near Giggleswick and Settle, my father and my uncle had to climb out of a window and struggle down a farm lane in six feet of snow to telephone the doctor; but they already knew that he could not come as the country road was blocked. Both my mother and I managed though without the doctor or midwife. Half of my cousins were born in the same bedroom in the same house there, beside a wood where the trees sighed and creaked in the wind, and rooks cawed and skylarks sang. In the house we had no electricity, and I would go round at dusk with my grandfather, lighting the paraffin lamps; it was one of my treats, as was walking down to the village with him, or running from the cold bathroom down to the living room and standing before the fire being towelled dry. In summer there were meals outside and swimming in the nearby river and cricket in the hay meadows and raspberries to pick. Then when I was six, my parents, my brother and I sailed away to the Seychelles, where it was hot and the sea was glorious, and I could run as free as I had in Yorkshire, but with fewer clothes on. In the Seychelles I went to a convent primary school – all the schools on the island were run by nuns and monks. I loved it. We had to work hard (my parents said that we had too much homework) but the classrooms were wide open all along one side and the sea was at one side of the playground. We used to sharpen our pencils with razor blades. Once, standing on one side of an old oil drum that served as our wastepaper basket, with a friend on the other side, both of us sharpening our pencils, her razor blade slipped off her pencil and sliced deeply into my elbow. It needed a lot of stitches. I turned this and many other adventures, (including dramatic brushes with gris gris, the local voodoo) in the Seychelles into my first children's novel Hill of Darkness. When I wasn’t swimming, or exploring the hills, or with my friends, I was up a guava tree, picking and munching the fruit while I sat on one branch and leaned against another, reading books, anything from fiction (especially Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights and Alice Through The Looking Glass, they were my favourites) to my father’s anatomy text books. Why anatomy text books? Because from the age of two I had wanted to be a doctor. That also meant that I had to go to a better secondary school than could be found in the Seychelles, so at eleven, I was sent to boarding school in North Wales. Travel was very expensive in those days and for two years I didn’t see my parents; after that I went home - first to the Seychelles, then to Lesotho when they moved there, and later still to Pakistan - to see them every summer for nearly three months (you have long summer holidays when you’re at boarding school) and occasionally for Christmas too. Although I missed my parents and the bright colours and smells of Africa and Asia, I wasn’t unhappy at boarding school. In the holidays I was based with my grandparents, and with my aunt and uncle and cousins up in the Lake District where we went walking and cycling. Meanwhile I read whatever books I could, but especially fiction. When I was sixteen though, I stopped wanting to be a doctor (I found physics and chemistry too much of a struggle), and concentrated more on history and Latin and English literature, all of which I loved. At university I read history, and then later on went to work in publishing in London. In 1976 I moved to Amsterdam . But the publishing job there was in a big company and I found that I didn’t like big companies (I was used to being in small, chaotic ones – much friendlier) so I left and became freelance, still in book publishing, and a few years later met my husband. Then in 2009 we moved back to the Yorkshire Dales to live in Settle where the book I'm now writing is set. About ten years later, I wrote my husband a love poem. It was about a mango. He said that I should make it longer, but I was indignant because I said I’d finished it. Then turn it into a novel, he told me. I tried it, and, to my great joy, a publisher took it. That wasn’t a children’s book, but I was lucky in that a children’s publisher read it and said that she thought I should write for children, too, about my own childhood – which was what I then did, two adult books later: Hill of Darkness. Other novels followed, both for grown-ups and for children. I don’t find it especially difficult to write, but it is difficult to find the time, and I have to be very disciplined about it. I leave my office in the mornings for one hour and go to a café or an inn, and I write there. It means that I am away from the telephone, from e-mails and from the post, and can concentrate on the words that are coming from my pen. Yes, that means that I write on paper with a fountain pen. Usually I change a lot, again with my pen, and then, maybe two weeks later, I’ll spend all evening, or all Saturday, typing it out on the computer. And then I often change it again – and again. So one book will take me about two years to write, even though none of them is very long. When I’m writing my children’s books, I get completely in the place that my main character is in, and, quite often, it’s as if I become my main character. When I was growing up, the most vivid time for me was between the ages of eight and eleven, and all my main characters seem to be that age. My stories tend to involve the hidden side of life, the mysteries, the world beyond our own. Usually, but not always, the names of my characters are from young friends of mine; in my latest book Leaving Home, Sam is the name of one of my godchildren. But the other names are names that exist in Mulanje, which is the village in Malawi in south-eastern Africa where the story takes place. Hill of Darkness was largely autobiographical, although I twisted the facts to make a strong story. For instance, the opening scene when Julia and Thomas bravely climb the gris gris hill at night in the Seychelles happened to me, but not at night. And the hill wasn’t in fact behind the house where my brother and I lived, but on the other side of the island, behind my friends’ house. And the bay where Thomas is in danger was in fact the scene of another tragedy which happened to my first boyfriend (but that’s another story). In most of my books, I borrow things from my own life and transform them or twist them into another story. So yes, I am always in my stories. In Leaving Home, I walked the paths in Malawi that Sam walked, I was at the tiny village where he goes, and, most importantly of all, I stumbled on the weird, spooky place that I describe (read the book!) and felt its power; in fact, it was because of that place that I started to write the book. I never know in advance what will give me an idea: it could be a place, as in this case, or it could be something I hear from a friend which then seems to take root in me and lead to ideas, or it could be something I read in a newspaper. In the case of The Rock Boy, for instance, I was in Malta where my parents lived for many years, when I read the story of two brothers who hid over the wheel of an aeroplane in Kashmir and stowed away till the plane landed in Cairo, where they were found (sadly, the older brother died); that, together with the refugees that were arriving at the island in tiny boats, gave me the idea for the book. Sometimes, curiously, it’s just a sentence which comes into my head when I’m cycling or walking or swimming that leads me into a story. The opening to the story is never difficult, and sometimes the ending comes quickly too (but at first I try to ignore it). But then you have to write the rest! Over the years I’ve written rather a lot of books; five, so far, for adults, and eight, so far, for children. I never know which is dearest to me; they all are. I’ve been lucky too in that several have been published in translation in other languages. One, Just Joshua, which won a prize in the Netherlands, has been published in Dutch, English, Japanese and German, and it was read out aloud on BBC Radio. The Rock Boy has even been made into a children’s opera. It was performed in Germany, in Leverkusen/Cologne in 2005, with a children’s orchestra, choir and soloists (six performances) and again in 2008 in Bonn in a completely new production (twenty-one performances). Another, Star over Amsterdam,was written as an oratorio and performed in Amsterdam by top soloists, choir and musicians, at Christmas in 2007; it’s set in Amsterdam which, in the story, has been invaded by American troops and Jesus is born there. My latest book Moorside Boy is set in ‘Seggleswick’ (which is actually Settle and in the village of Giggleswick across the river). It’s a story partly in the past and partly in the present. Without giving away the plot here, I can say that it’s for all who know and love Settle, as there are plenty of local places in the story (Settle Primary School, St Alkeda’s churchyard, Settle market place, Nelson the shoemaker, and so on). It’s partly in the present, and partly in the past. In the story, I have borrowed details from the life of Benjamin Waugh ‘the children’s friend’ who was born and brought up in Settle in the nineteenth century, and who went on to found the NSPCC. For that reason, I’ve decided to give all proceeds from the sale of the book to the NSPCC. William Golding is the writer that I most admire (his most famous book is The Lord of The Flies; if you haven’t read it yet, try reading it now); sometimes, when I’m about to start a new book, I read one of his, just to encourage me in my own writing. But the best book ever, the richest in every way, is the Bible. It is packed full with stories, some historical, some mysterious, some bloodthirsty, some inspiring. It’s packed full too of emotion. And when you think what it has meant to people down the ages, it’s stunning. Then, after that, if I had to choose two books to be locked in a room with for ever, the other would be the complete works of Shakespeare, because the poetry of his plays and his thinking are so wonderful. I could never get bored with either of those two books – and think how long they both are too! I also love books by A.A. Milne, Lewis Carroll, Tony Ross and Michael Morpurgo. I don’t illustrate my books with pictures; the best person to illustrate them is you, the reader. What I try to do, is to paint a clear picture with words, so that you see the people and places that I describe in your mind. When I'm not at work or writing my next book, I love to walk on the moors, to go for a bike ride, to travel, to swim (preferably out of doors), to read, to cook and eat with friends. The best advice that I can give you if you want to be a writer? Read books, love books, and live life. |  | ||

| |||

| |||

| |||